The Power of the Cube

Let’s get back to our goal of doubling your business leadership capacity.

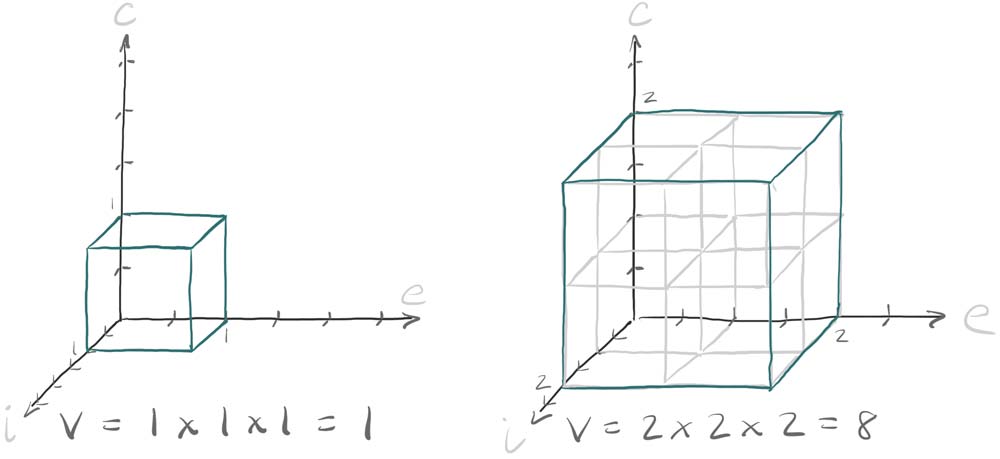

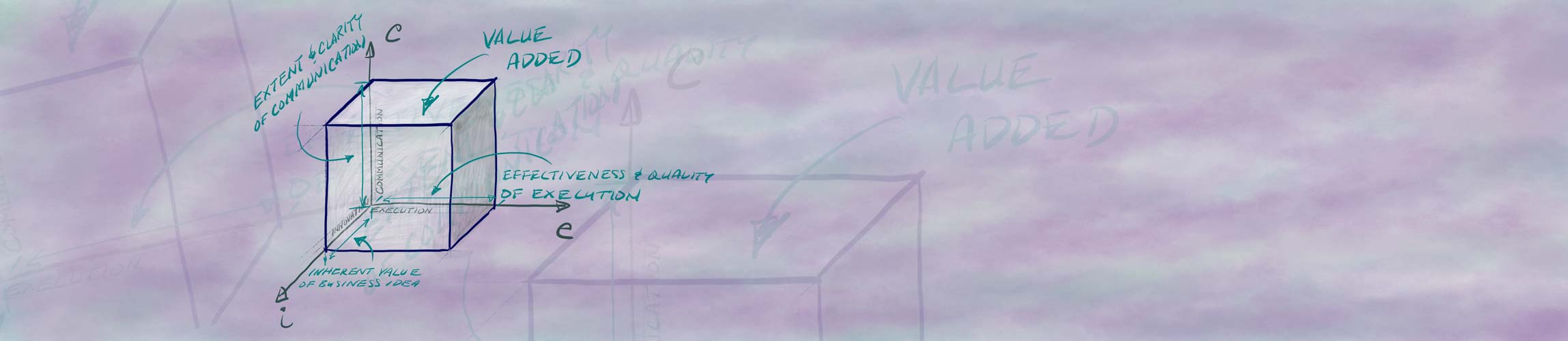

Innovating, Communicating and Executing aren’t exactly “ingredients.” We’ve learned from visualizing the ICE Cube that they are “dimensions.” What difference does that make, you ask? A BIG one. If business leadership is like a cake that you are trying to bake, and you want to have twice as much cake, you would have to double each ingredient (innovation, communication and execution). You would have to get twice as good at each. But let’s look at what happens if you did.

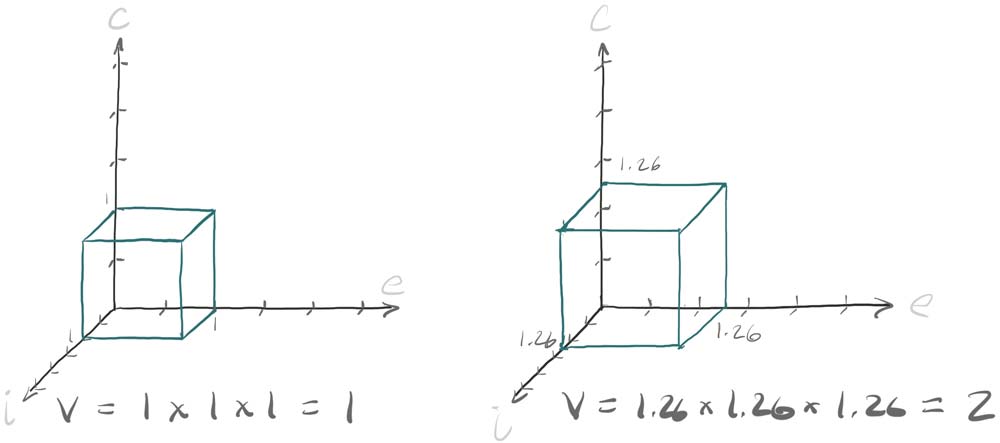

If you get twice as good at innovating, communicating and executing, your business leadership capacity will be eight times as big! We’re not trying to make you eight times as good in one year. Twice as good is hard enough. So how much better do you have to get at each dimension to be TWICE as good at adding value?

1.26 times better. Or 26%. Barely over one quarter. What this shows is that making incremental improvements to each dimension can lead to very big improvements in the volume those dimensions create.

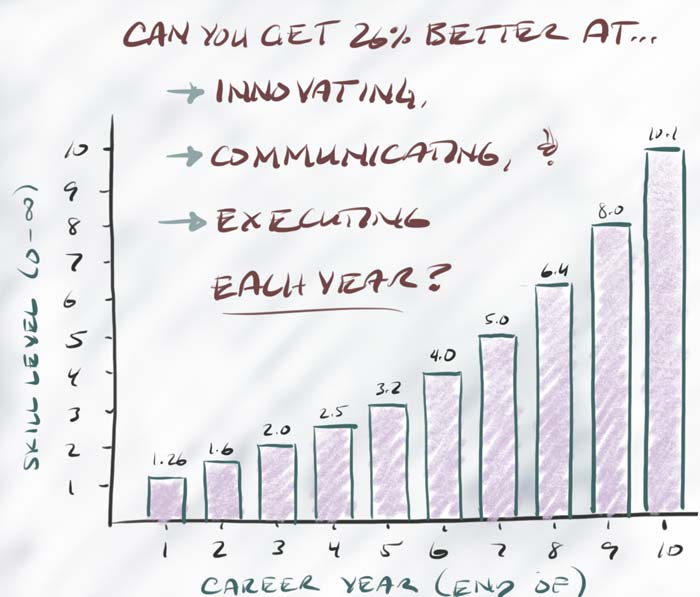

Over the course of time, if you keep getting 26% better at each dimension, after 3 years you will be twice good, and after 10 you will be 10 times as good. Remember, that’s 10 times as good at each dimension; innovating, communicating and executing.

Let’s recap how you will keep getting better, faster and faster, at each of these three dimensions.

- As we discussed in ‘Rethink Learning,’ the more knowledge you have, the faster you will learn, especially if what you need to learn is related to what you already know, and in business, it always is.

- You will be focusing more and more of your energy on solving business problems which will dramatically increase the amount of exercise your Six Basic Action muscles receive.

- As you learn and demonstrate the ability to solve bigger and more complicated problems, the problems you are given to solve will be getting dramatically bigger as well, which will expose you to more learning opportunities, greater incentives to learn, and more resources to learn from.

- As you get promoted – which you will whether you make an effort to or not as long as you keep adding more and more value – you will have greater access to resources to learn from and greater access to business situations that will generate learning.

It is definitely possible to get ten times as good at something in 10 years, especially if that something complicated like innovating, communicating and executing. And given business is essentially infinitely scalable, especially if you work in a large corporation or in a company that is rapidly growing, you will never run out of bigger and more complicated business problems to solve.

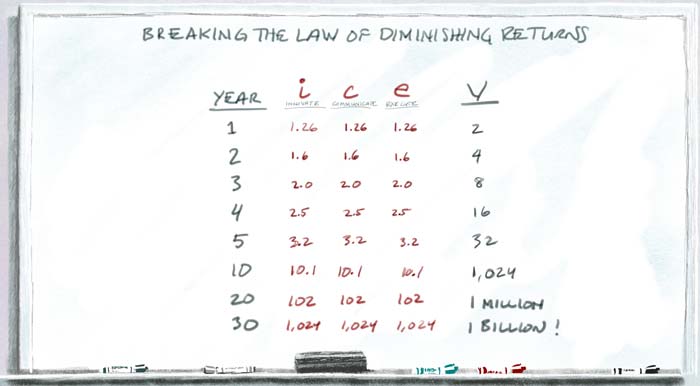

What is truly amazing, though, is what that 10x improvement in each of the value dimensions does to your business leadership capacity, meaning your ability to add value. By the end of year one, when you are 26% better at each of the three dimensions, you are now TWICE as good at adding value. By the end of year three, when you are twice as good at the three dimensions, you are 8 times as good. And by year ten, the ten X improvement in each of the dimensions becomes a 1,000 X improvement in your ability to add value.

Over the course of a 30 year career, if you keep getting just 26% better every year at innovating, communicating and executing, that math starts to get crazy. Just like trying to draw Bob’s learning curve for 30 years would take a piece of paper the size of a basketball court. By the end of year 20, if you succeed at getting 100 times as good at innovating, communicating and executing that will make you 1 MILLION times better at adding value. By year 30? 1,000 times better at innovating, communicating and executing would make you 1 BILLION times better at adding value!

That’s a little hard to imagine, and I’m not sure anyone has ever succeeded at getting 26% better at each of the three dimensions every single year of their career. Keep in mind, no one has ever even tried, because no one has ever thought precisely along these lines. The world’s greatest business leaders were not consciously trying to get better and better at innovating, communicating and executing. They were trying to solve the most pressing business problems that stood in the way of them making their companies more valuable. They were working their butt off to figure out the next right thing to do, and then working their butt off to get it done. In doing so they got a lot of practice understanding, designing, listening, explaining, deciding an acting. And that practice made them get exponentially better at innovating, communicating and executing.

And that allowed them to perform amazing feats of value creation. Let me give you two examples.

In the early 2000s I was fresh off GE’s Corporate Audit Staff and Director of Business Development at GE Americom, a division of GE Capital that had a fleet of satellites in geosynchronous orbit with big communications payloads. GE Americom made money by leasing their communications transponders to cable head ends, internet start-ups and telephony companies. It cost them hundreds of millions of dollars to build and launch a satellite into orbit, so any proposals for new satellites had to be signed off by GE’s investment committee. And the chair of the investment committee was Jack Welch himself.

Robert Green, a good friend and the CFO of GE Americom at the time had just returned from one such proposal meeting and told me what he thought was a hilarious story. The Europe team was seeking $450 million from the investment committee to launch a satellite into an orbital slot that would provide excellent coverage of Great Britain and much of Europe. What Robert found so funny was that almost before the presentation got off the ground Welch had already flipped to a financial spreadsheet on page six or seven and inquired what a number in one of the dozens of rows and columns on the spreadsheet represented. It was the revenue they expected the British cable industry to generate for the satellite. But before they even started to answer, at least as Robert told it, they apologized, packed up their presentations and said, “It looks like we have a little more work to do.”

The fatal flaw that Jack discovered that an entire team of satellite experts did not had to do with the fact that this satellite was depending on that British cable revenue to turn a profit. It was the biggest revenue driver in the entire plan. That by itself was not a big issue. The big issue was that the three biggest cable providers in Great Britain - Sky, Telewest and NTL - had just begun a price war and that most analysts believed only two cable providers would survive. And Jack knew from previous experience in other parts of GE that the suppliers of companies in price wars fare almost as poorly as the warring companies themselves. As these cable operators slashed prices to compete for subscribers, what they could afford to pay GE for satellite transponder time would plummet as well. If that wasn’t reflected in the financials Jack was looking at, there was no way it was going to make a profit.

Jack knew about the price war because it was also a big issue for NBC, another business that GE owned at the time. And Jack was a master of connecting all the dots between his companies. He organized every part of GE’s operating system to help him understand everything that was happening in the world just so he could make connections like this one. So when he saw the biggest revenue number on the revenue spreadsheet was from British Cable it was an obvious question for him to ask. And as soon as he asked it a horrible epiphany popped into everyone’s head, “No, I don’t think we took that into account.” Some on the satellite team may have been tangentially aware of the emerging British cable battle, but if any had connected the dots, they didn’t get the message to the person doing the financial analysis. There are a lot of details to keep track of when making a $450 million satellite proposal.

Somewhere along the line Jack became almost incomprehensibly good at zooming in from the big picture to the tiniest detail and then zooming back out to figure out what it meant. In this case it meant no satellite. In the ten minutes that it took for Robert Green to add another funny anecdote to his arsenal – most of the great leaders I know from GE are great story tellers -- Jack Welch had just saved GE a lot of money. The entire $450 million satellite would not have been a loss. But without being able to hit the revenue numbers they were projecting for British Cable, and having no way to reconfigure the satellite in anyway after it was launched, Jack had probably avoided a $200 million loss vs. the return that $450 million would make somewhere else in GE. Did Jack Welch have to be a billion times better at adding value than he was when he started his career at GE as to do that? I’m not sure how to do that math. But $200 million in 10 minutes is a lot of money in not a lot of time.

In a similarly remarkable act of value creation, Elon Musk, in the course of about three weeks, saved Tesla from impending bankruptcy. The Model S, Tesla’s only car at the time, was suffering horribly from infant mortality quality issues and sales were plummeting. Only months before it was named Car of the Year by Motor Trend and Musk had just moved production to a new, expensive, mega factory. If sales kept dropping Tesla would run out of cash and go bankrupt in less than a month. Elon’s plan to save the company was to sell it to Google. To keep it afloat in the meantime, Musk fired a number of senior executives who had hidden the production issues from him, promoted less experienced but eager executives to replace them, and pulled employees from every part of the company to convert pre-orders into sales and fill the factory. The moves must have seemed the last desperate throws of a young CEO who’s oversized ego had finally caught up to him.

But in the time it took Google’s lawyers to review Musk’s proposal, his ‘last desperate throws’ were so successful that the company not only filled the factory generating the cash it needed to stay afloat, it turned its first ever profitable quarter. And the in the next 6 months, the value of Tesla rose from the $6 Billion Google wasn’t willing to pay for it to a market cap of over $30 billion – a price Google could no longer even afford. Was Elon Musk a billion times better than a recent college grad at running Tesla? Who knows, but $30 billion is a lot better than bankrupt. At the time of this writing, Tesla is the most valuable car company in the U.S., worth more than GM, Ford, or Honda.

So maybe the concept of getting 1,000 times, or 1 million times, or 1 billion times better at business leadership is not any more far-fetched than what real business leaders actually do every now and then. But that doesn’t mean that if you grow your business leadership capacity by 1000 times people are going to think, “Wow, that person is 1000 times better than me!” Or even, “Wow, that person is 1,000 times better at leading than they were the last time I saw them!” It just means you’ll be 1,000 times better at adding value. We can use math like this to describe business leadership because the objective of business leadership is adding value, and we can count business value in terms of dollars. How much better at leading did Martin Luther King, Alexander The Great, or Margaret Thatcher get over the course of their lives? Who knows. You can’t put a number on it because you can’t put a number on the kind of value they were adding.

And whether or not you will be 1,000 times better in 10 years, 1 million in 20 or 1 billion in 30, and what exactly that means, is not the point. The point is that if you want to get better at business leadership, the fastest way to do it is improving your ability to innovate, communicate and execute by mastering the six basic actions of business leadership.