Strengths or Weaknesses

In the real world it doesn’t make much sense to try to get exactly 26% better at innovating, communicating and executing. First, they can’t be measured that precisely. Second, getting better at everything at the same rate at the same time is not very practical. So how should you go about making your box bigger?

There is actually quite a bit of debate on the topic of what we should focus our improvement efforts on. And what answer is fashionable seems to fluctuate every ten or 15 years. The debate focuses on whether you should focus on your strengths or your weaknesses. On GE’s corporate audit staff, one of the most respected leadership engines in the business world, we focused heavily on improving our weaknesses, or “development needs” as we called them. Every 2 months associates and leaders alike would be run through rigorous 360 degree performance evaluations. These evaluations would identify three to five top strengths and three to five top development needs. We didn’t spend much time on strengths, and my manager made it clear that I needed to fix every development need I had before the next review. Yes, I would have 3 to 5 in my next review as well. But they better be new ones. GE took this approach so seriously for its auditors and top leaders that the assignments people received were based in large part on what their development needs were. Your next assignment would stress your weaknesses. You either fixed them or your failed. Not good at critical thinking? Your next assignment will require in depth financial modelling. Not good at managing complicated tasks? Your next assignment would be to implement a cross business strategic initiative.

This worked wonders for me and all of my peers. It was hair raising and made it feel like I was never more than a week from being fired, but I learned to get good in areas where I had very little talent, very quickly.

But the turn of the century brought a 180 degree turn in thinking on this subject. And it came with a remarkably insightful book, “Now Discover Your Strengths,” by Marcus Buckingham and Donald O. Clifton. That book observed that the vast majority of value that one creates comes from their strengths. It is also much easier to improve a strength than a weakness. So why waste precious energy grinding away on weaknesses that you don’t even use to add value. Buckingham and Clifton’s arguments were compelling and the world came to follow their thinking. The backbreaking work of getting better at what you suck at was thankfully banished.

But why, then, was the GE audits staff, with its “grind your face off working on your development needs” mentality, so effective at producing exceptionally proficient business leaders like Bob Swan? It turns out that BOTH philosophies are SIMULTANEOUSLY correct. And it is almost obvious when you visualize the problem through the lens of the “ICE Cube.”

Let’s say you are incredibly gifted at getting things done. Maybe in the top four or five folks at executing in your entire company, which let’s say has 1,200 employees. When a top leader in your company needs to get a critical project done they immediately ask your boss if you have the bandwidth to lead it. Let’s give you a number to represent your skills at executing.

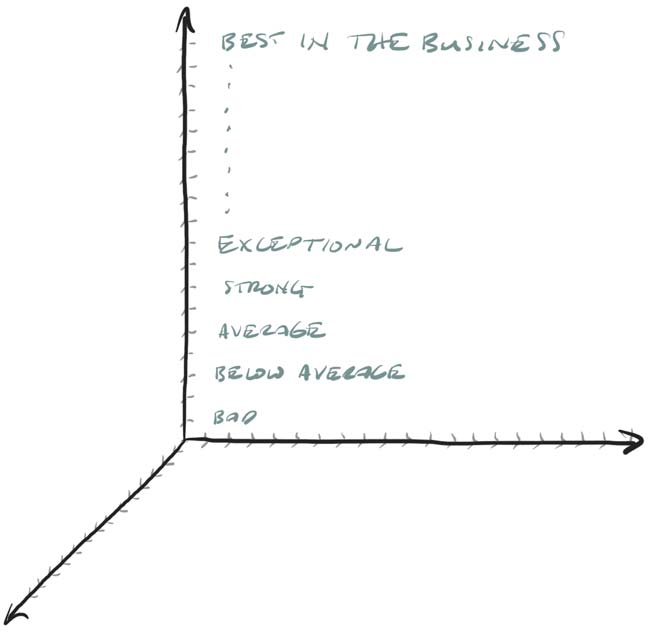

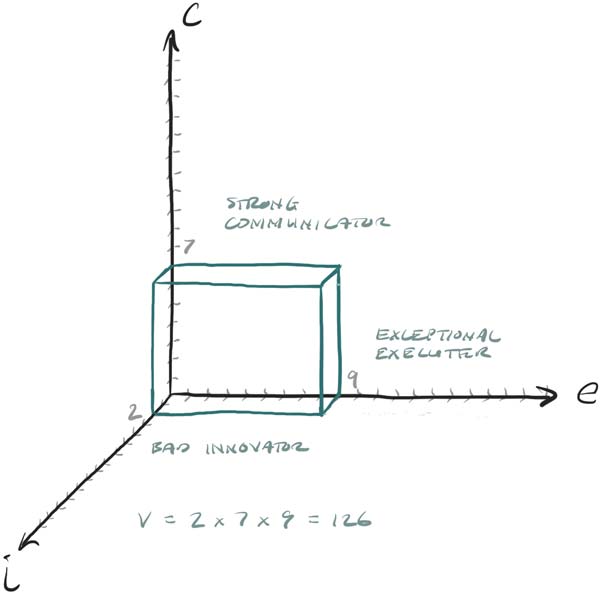

The scale is zero to infinity as you can get infinitely better at each of the dimensions. But we’ll keep the numbers manageable. Some people can get overwhelmed by the simplest of tasks, they would be a 1. Others can manage a multibillion dollar airport construction project. They would score a very big number, 50 or 100 or 1,000. But no one in your company can manage projects that big, and you’re one of the best. So let’s say you are a 9. You are also great at communication. Among the best of your peers, but there are lots of more senior folks with better skills. Let's call you a 7. But you are not really a creative type and are pretty unskilled at innovation. You like to avoid idea discussions all together and nothing would pain you more than sitting through a brainstorming session. You are a 2 at innovating. Most of the people you work with are much better at this than you.

You want to double your business leadership capacity, right? Let’s do the math and figure out what it is...

V = 2 x 7 x 9 = 126.

If you want to double it you need to get it to 252. That would be a pretty massive leap.

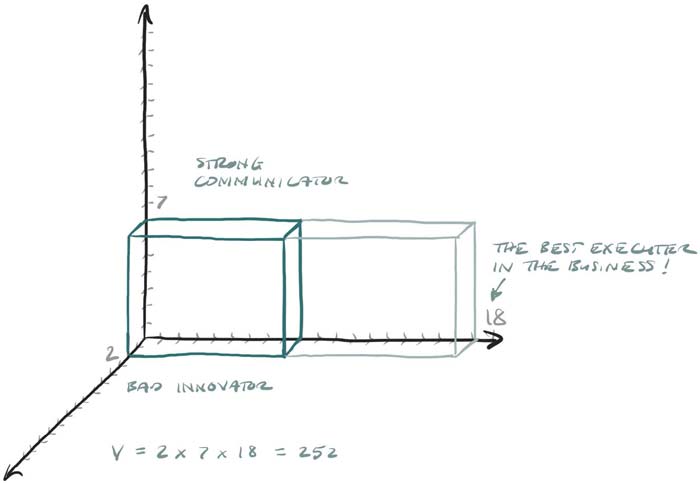

Let’s say you can only improve in one dimension, though. Which one should you focus on?

The “Focus on your strengths” school of thought would say, “Focus on your strengths. Double your ability to execute.” But let’s think about that for a minute.

Doing that would mean you would have to go from being a 9 – which is already one of the very best in your entire company – to an 18! Way better than the best most likely. That would be very difficult to do in one year. Who could you find to be your mentor? They would have to be incredibly skilled. What other resources could you find to help you? Given you are already very good at executing in the real world it would be difficult to find books that cover material you don’t already know. You would, in effect, be going from extremely good to TWICE AS EXTREMELY good. That sounds hard, doesn’t it? Even getting twice as good at Communicating in one year sounds hard. You are already pretty darn good at that too.

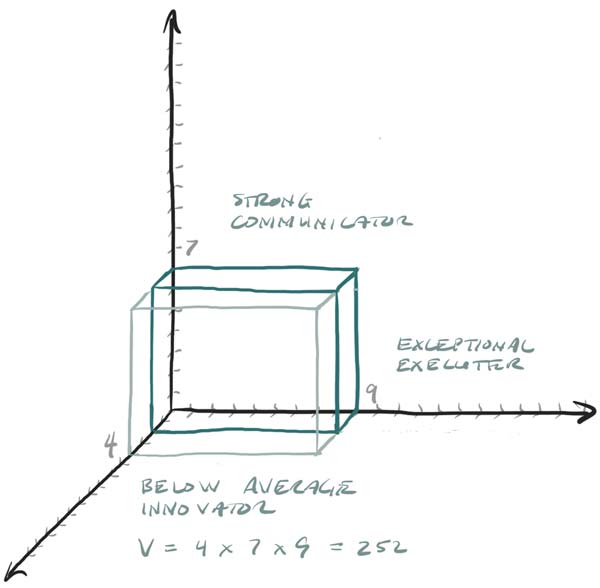

The ‘focus on your development needs’ school of thought would suggest you try to improve at your weakness, innovating. Let’s think that through the same way.

The bad news is you suck at it. Always have. But the good news is also that you suck at it. To get twice as good at it you only need to get to a 4. Go from being really bad to being just a bit below average. And guess what, almost anyone can be your mentor. Lots of books that cover the basics of innovating or subjects related to it would be enlightening for you. You probably just aren’t approaching it the right way. Or in fact avoiding it to hide the weakness which is inhibiting both your ability to add value AND your ability to get better at it.

So notice that doing either, getting twice as good at your strength or you are twice as good at your weakness, doubles your business leadership capacity:

I personally would rather try to get my weakness from a 2 to a 4 in a year than my strength from a 9 to an 18.

So it sounds like Marcus Buckingham and David O. Clifton got it wrong, then. Right?

Not quite. What Marcus and David were really pointing out is that you should focus on your strengths to ADD VALUE. In our example above, your 9 in execution and 7 in communication are adding much more value to the business than your 2 in innovation. The business has lots of other people that are innovative that can produce the ideas that you communicate and execute. Focusing on your strengths when you are adding value is exactly what you should do.

But when you are trying to get better, you should focus on your weaknesses. The higher up you go in an organization the harder it will become for people to tell you that the idea that you are masterfully selling and executing is a bad one. The higher you go the more damage your weaknesses will produce. They never need to become your strengths and they won’t, but you can’t let them become a liability. If and when the careers of talented individuals flame out, it is almost always because the gap between the strongest dimension – the one that got you the big promotion – is too far ahead of the weakest dimension – the one that gets you fired.

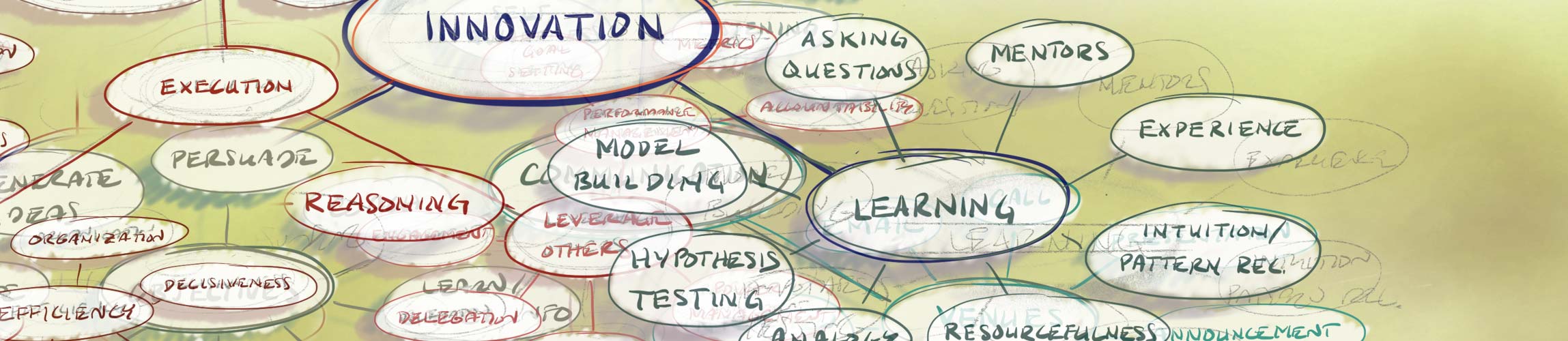

But notice the only skills we are talking about are the dimensions of innovating, communicating and executing. Marcus and David were talking about all of the possible little things that business leaders do that one can get better at. The sub-skills that the six basic actions and the three dimensions rely on. Let’s say the things you are worst at are time management and organization. These are critical to being a good executor. But let’s imagine you are really good at executing despite these handicaps. You just have your own way of winging it and it works. Should you focus on improving your organization and time management skills? Absolutely not. They are not making you a weak executor, so who cares? They are not preventing you from adding value. There are lots of little subskills that can make you better at each of the dimensions (more to come on this in chapters I am working on now). You don’t need to be good at any particular individual subskills. You just have to be good at innovating, communicating and executing.

Also notice that the reason you are already so good at what you are good at is because you are already learning how to do it very quickly. It is an area that you have interest and talent in. You will continue to get better at it, especially if you take Marcus and David’s advice to put energy into DOING it as often as possible to maximize the value you add to the business.

So the answer to the big question, “What should I focus on, my strengths or weaknesses?” is a resounding, “BOTH.” Add value today by leveraging your strengths, and increase your ability to add value tomorrow by improving your weaknesses. And by strengths and weaknesses I really mean dimensions. Operate in the dimension of your strengths, improve on the dimension of your weakness.