The Swan Curve

In 1995, just the second year of my career at General Electric, I was called into the office of a gentleman named Bob Swan. What he told me changed the trajectory of my career in many ways, some of which I’ve only recently recognized.

Bob was a rock star at GE. He had just come off an epic, six-year stint on the Corporate Audit Staff (CAS), GE's problem solving 'special ops' team and ultimate leadership development track. Jack deployed CAS as a lever of change all over the globe to implement strategic initiatives, solve emerging business problems and verify GE’s hundreds of billions of dollars in assets. Bob, after finishing the grueling 5 year program that only 2% of CAS associates survive, was asked to stick around for a 6th year to run the whole operation. Having just completed that assignment, he was now the CFO of GE’s billion dollar revenue locomotive manufacturing business. At only 32, he was the youngest division CFO in all of GE.

I, on the other hand, was a manufacturing management trainee in that same division. I had just run the two year gauntlet required to get a one month ‘pilot’ on CAS. The pilot was a trial assignment that everyone had to pass to officially become a 1st year associate. The success rate was 50%. Bob barely knew me, but less than seven years earlier he had completed his own pilot. And he wanted to give me some advice.

What Bob drew was his learning curve

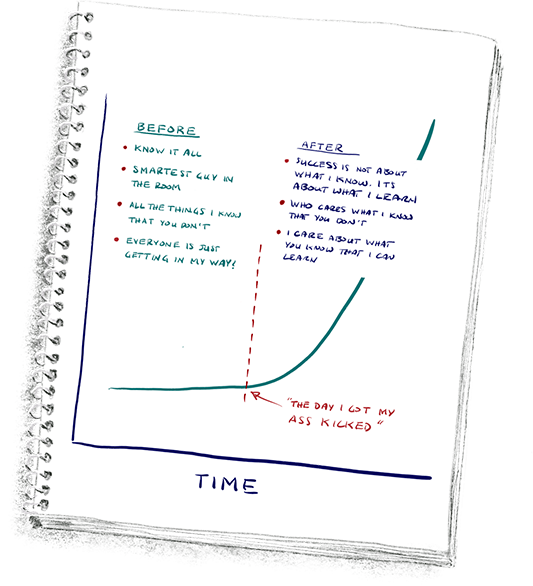

Bob drew a graph on a piece of paper as he started telling me about a formative experience he had 5 years before. He described it as “getting his ass kicked.” He told me that for his first 18 months on staff, he was arrogant. He thought he knew it all. He always felt he was the smartest guy in the room. But apparently during month 18 of his tenure on staff he screwed something up. He didn’t specify what, but it was bad enough that it led someone well above Bob in the chain of command to sit him down for a very uncomfortable conversation.

I later came to know this kind of conversation as a, “Let me break this down for you,” discussion. These conversations start with, “Let me break this down for you.” And they end with the recipient finding a completely different attitude or finding somewhere else to work. Bob apparently found the former.

What was ‘broken down’ for Bob was that even though he might be exceptionally bright, he wasn’t as smart as he thought he was. That his future success depended less on what he already knew than what he could learn from that day forward. And even more so, how fast he could learn it.

Bob told me that after that discussion he approached his career differently. It was as if a switch had been flipped. He never again thought in terms of what he knew that others didn’t. He thought instead about what others knew that he could learn. No matter who it was, no matter what their position. He told me that someone that knows it all has nothing left to learn. And if you are not learning in a company like GE, you’re an idiot.

The line he had drawn for me was his learning curve. Almost flat for the first 18 months, and after that discussion, ever closer to vertical. He told me not to make the same mistake he did.

“Start learning, as fast as you can, the second you walk out of this office. Don’t wait 18 months like I did. And don’t forget...

“It’s hard to be the smartest guy in the room if you’re an idiot.”

23 years later, I’d like to think I know a lot more now than Bob knew then. That was a long time ago and my own ride on staff went pretty well. And that ride led to lots of other rides in businesses all over the world, with all kinds of neat problems to sink my teeth into.

But Bob’s curve subtly and profoundly shaped how I thought about my career – to be humble, to rely on everyone to find solutions, to always be learning, and that it’s much better to be the person with the best questions than the person with the best answers. Recently I decided to take a step back and review my career from the very beginning to try to accumulate and distill everything I’ve learned. In doing so I discovered two deep insights embedded in Bob’s graph that I hadn’t noticed before. I’m not sure Bob even realized he had put them there when he drew it. But they were at the core of what made him successful. They were at the core of what makes every great business leader successful.

They were the answer to a question I had been looking for my entire career: “What is it that differentiates the very best business leaders from everyone else?”